“What doesn’t kill you only makes you stronger.” (WDKYOMYS)

Imagine being told at just under 4 years old that you were the “man of the house” when you had no idea what those words even meant. Well that is a part of my story. Not even four years old and according to the rules of my tradition, I was above my mother and grandmother with whom I lived forced by circumstance to “be a man” when I was just a little boy. The rules were simple. Be strong or die. And so, rather than allow myself to be destroyed by what I faced–and it was a lot–I became stronger and stronger and stronger.

My Name Means Rock for a Reason

The name Pedro means Rock. And in many ways, I can resemble that name if I am not mindful to remember the lessons life has taught me.People can’t tell from looking at me now or how I tend to carry myself. But, I can tell you in no uncertain terms that if most Americans experienced what I went through in the first 16 years of my life, they would probably be dead or someone else would be. But, in part, because of my almost religious devotion to the notion that what didn’t kill me, made me stronger, I am still here today. And yet, I can tell you now that WDKYOMYS is often the worst advice anyone can give a person in pain.

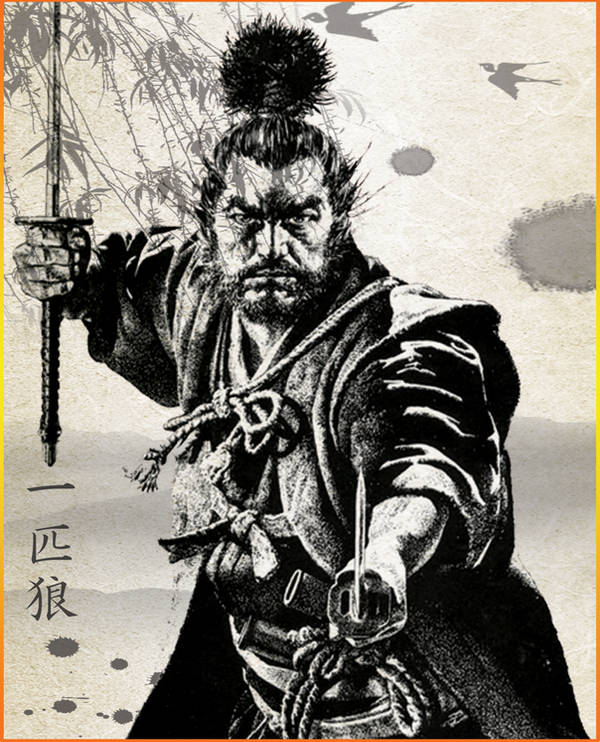

For a long time, I was, what I would now say is, too strong. So much so that people close to me began to think that I didn’t have feelings. They didn’t understand how I was able to keep pressing forward under conditions that would have broken them. And so for many, I became un-relatable, something that I experienced as their problem and not mine. And then, one day a friend gave me a copy of the Japanese classic, Musashi by Eiji Yoshikawa. When he handed it to me, he said, “This is you.”

One of the key lessons in Musashi is the danger of untempered strength. Musashi’s early arrogance and reliance on brute force often alienated him from others, showcasing how unchecked power can isolate a person and blind them to the subtleties of human connection. As Musashi matures, he learns that true strength lies not in domination but in self-restraint and understanding. Yoshikawa illustrates that a person can be “too strong” when their power overshadows empathy and balance, leading to harm rather than harmony. This lesson is central to Musashi’s transformation from a feared swordsman into a figure of profound wisdom and humanity.

In my case, my strength didn’t come from brute force. I’m a small guy. Rather, my strength came from my willingness to die–something I learned that most people fear more than anything. Because of way too many adverse experiences, by 12 I became convinced that I would never make it to age 18. And so, I decided to embrace it, to live each moment as if it could be my last. My only concern was that I could face death with my eyes open and unafraid. My goals were simply to live in a way that my grandmother wouldn’t be ashamed at my funeral and to not die as a coward. So with these two commitments in my mind and the belief in WDKYOMYS, I, unbeknownst to myself, became a force.

I can’t even describe to folks who know me now how intense I used to be as a disciple of WDKYOMYS. But, perhaps this illustration will serve. In one instance, my brothers and I were walking through our neighborhood when my brother pointed to one of the most well-known drug dealers and told me that he had stolen his hat and that at that moment the hat was on the drug dealer’s head. Being completely unconcerned with dying and almost frustrated that death was taking so long to get me, I courted it by walking up to the pharmaceutical rep and snatching the hat off of his head without saying a word and simply handed it to my brother and kept on walking.

Of course, our neighborhood purveyor of a panoply of Purdue-like products, got pissed. He jumped up and got in my face and told me I was going to get myself killed. He didn’t realize that I had accepted that long ago. But, he could tell from the look on my face–or lack of one–that I was not concerned in the least. I simply told him that as a drug dealer, he should have enough money to not need to steal a poor kid’s hat. To which he responded that he, in fact, did not steal my brother’s hat.

Hearing this, I looked over at my brother and he sheepishly confirmed that I was actually the person who just stole the innocent crack dealer’s hat. Oops. It turned out that my brother had misplaced his hat and when he saw a similar hat on the young man’s head, he thought it was his. It was an honest mistake. At least that is how I took it. So, I took the hat out of my brother’s hand, put it back on the wannabe kingpin’s head and walked away while the drug dealer yelled back at me to watch myself. It would be a while before I took his advice.

Reading Musashi really rocked my world. With that one recommendation, my friend communicated so many things to me. The first was that he really saw me. This was something that I was not used to. The second was that I was missing something critical in how I showed up in the world and in relationships. As much as I hate to admit it, being vulnerable is a critical component to embracing the full import of being human.

Because of his intervention, for the first time in a long time, I realized that I should care if I lived or died because at a minimum, ignoring my own vulnerability only worked to hyper activate the vulnerabilities of those who cared about me. After all, I was well past 18 years old at this point. Perhaps that POV had served me so that I could make it through my neighborhood. But, it had hurt me everywhere else because by being willing to ignore my own pain, I was communicating to others that I didn’t care about theirs either and it was a weakness for them to care about theirs too.

In fact, I literally used to say, when I thought people were using their feelings as an excuse for behaving unreasonably, “I am not concerned with your feelings anymore than I am concerned with my own.” At the time, I thought saying things like this was helpful. After all, wasn’t America built as an altar to the King of WDKYOMYS–the way Jesus is taught in American many churches? But, I was beginning to see how wrong I was.

Greater Strength Through Weakness

This really hit home for me in seminary when one of my professors took direct aim at the fallacy of WDKYOMYS. He told the whole class how much he hated it when people said that. He said that it was completely contrary to the teachings of Jesus, lacked compassion, and that, in his opinion, a more accurate statement was “Sometimes what doesn’t kill you messes you up so bad that you wish that it did kill you.” And he added to it that when we come to that place, it is only then, that we can understand the reality of grace–what Paul described as God’s strength being made perfect in human weakness (2 Corinthians 12:9).

By way of example, he pointed to Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane praying so hard that, according to the tradition, he experienced hematidrosis, a rupturing of tiny blood vessels near the sweat glands, often triggered by extreme stress or physical exertion. According to my professor, Jesus was literally scared to death. And it was because he was able to admit that to God in vulnerability that he was able to receive the grace to go forward despite his fear. In other words, Jesus wasn’t perfectly strong, he was perfectly weak and that only someone who can admit that and embody that can truly follow Jesus’ teachings

I had never heard anyone explain this idea before. But, I instinctually knew that it was correct and something that my heart had been waiting to hear for a long time. Even before my friend gave me the Musashi book, I had glimpses of this awareness when I lost a child. I had prayed that my child be saved and even tried to bargain with God as we often do when we fall back on immature understandings of faith and how the world works. But, when the answer I received was no, rather than fall apart like I wanted to, I made the mistake of becoming stronger just like I built the habit of doing. And when I became stronger, I unconsciously deepened people’s belief that I didn’t have feelings about the one thing I felt more deeply than I had anything in my life up to that point. Again I was too strong.

It would take 20 years for me to let myself cry the way I needed to all of those years ago and 40 years for me to really thank my three your old self for surviving and doing his best and to release that part of my that held myself responsible for not being able to be a man at that age–something I could never have possibly succeeded at. And now, I have come to a place where I can share the wisdom of honoring our weaknesses with others.

In the American context, we are addicted to the illusion of the rugged individualist and the idea that if we can’t do something on our own then it is somehow deficient. This very notion is a fallacy of the greatest proportions. The reality is that no one can do anything on our own and we are all part of an interconnected network of relationship inseparable from all that was, is, and shall be. Words cannot express how grateful I am to have lived long enough to learn from my mistakes and to look back on past errors–even those celebrated by the status quo–and see them through the lenses of the wisdom that comes with knowing where I am weak. It is my hope that in sharing this, you too will consider how being too strong can become a weakness and how embraces our weaknesses can become our greatest relational strengths.